Why Organic Agro Exports Are Trending in 2026

Key Highlights

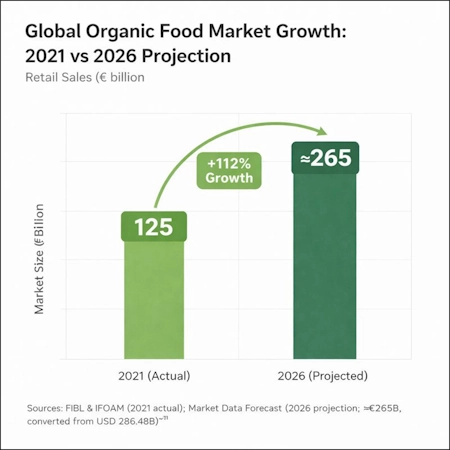

- Organic isn't niche anymore — it's already a €125 billion market and heading toward ~€265 billion by 2026. That's a real scale, not a side segment.

- Demand is concentrated where it matters most — US and Europe — which means exporters know exactly where the buying power sits.

- Supply isn't the bottleneck now. With 3.7 million producers worldwide, the product exists — it just needs better aggregation and logistics.

- Trade is already happening in bulk. Nearly 4.7 million tonnes move into the EU and US every year. These are container loads, not specialty parcels.

- Europe continues to act like the main gateway. Get into ports like Rotterdam or Hamburg, and half the continent is within reach.

- It's everyday staples driving volumes — cereals, fruits, coffee, cocoa, oilseeds — not fancy boutique items. Steady goods, steady business.

- Buyers aren't “testing organic” anymore. It's becoming routine procurement, just another line in the sourcing plan.

- Bottom line: this isn't hype. The numbers simply add up. Bigger demand + growing supply + smoother trade routes = solid export opportunity.

Introduction:

Organic used to be spoken about like a philosophy. Now it's spoken about like freight. The language has changed. Earlier it was soil health and sustainability. Today it's tonnage, contracts, and shipment schedules. Somewhere along the way, organic stopped being a side conversation and quietly joined the main trading floor.

And when you look at the numbers, the shift makes sense. Keep reading this informative piece of blog if you are an organic food trader .

The market has crossed the point where size alone drives trade

At nearly €125 billion in global retail sales, organic food is no longer a premium corner of the supermarket. It's an economy by itself. According to Market Data Forecast, this market is projected to reach USD 286.48 billion (approximately €265 billion) in 2026.

The United States alone accounts for €48.6 billion, followed by Germany at €15.9 billion and France at €12.7 billion. Once demand hits this scale, supply chains naturally stretch across borders

- Buyers don't treat organic as an experiment anymore; they budget for it like any staple food category.

- Large supermarket chains require year-round supply, which automatically pushes procurement toward bulk imports.

- Organic food exporters are always after predictable volumes instead of seasonal spikes like any other suppliers. Indeed, they seek long-term contracts.

- At this size, trade becomes practical — less ideology, more logistics and margins.

Supply isn't scarce anymore — it's everywhere

There are now massive almost 3.7 million certified organic producers all around the world. What's interesting is most of them are based out of Asia, Africa and Europe.This enormous number keeps rising each year. So the issue isn’t availability. It’s coordination. Organic supply today feels less rare and more scattered

- Millions of small farmers mean plenty of produce but. But this is in fragmented lots that need a lot of systematic aggregation.

- Countries like India, Uganda and Ethiopia lead in producer numbers, expanding the raw material base.

- Organic food exporters and processors become essential middle links between farms and global buyers.

- For traders, the work is no longer “finding organic,” it's organising it efficiently.

Cross-border trade is already measured in millions of tonnes

This isn't future potential or theory. The EU and the US together imported nearly 4.7 million tonnes of organic products in 2021. That's bulk cargo. That's full vessels. Organic is already moving like conventional commodities

- The EU imported around 2.9 million tonnes, while the US brought in 1.8 million tonnes, showing consistent structural demand.

- These aren't specialty shipments; they're scheduled, repeated flows.

- Once imports reach this volume, trade tends to stabilize rather than shrink.

- Exporters entering now are joining an established highway, not building a new road.

Europe remains the main gateway for organic food suppliers

If you follow the cargo routes, Europe sits at the center. The EU's organic imports alone reached 2.87 million tonnes, up 2.8% year on year. The Netherlands acts as a redistribution hub, quietly channeling shipments across the continent

- Rotterdam and surrounding ports function like entry points for half of Europe's organic trade.

- Germany continues to be both a major importer and consumer market.

- Growth may be steady rather than explosive, but steady demand is what organic food suppliers prefer.

- For many suppliers, getting into Europe is still the first real milestone.

It's everyday staples that carry the volume

Organic trade isn't driven by boutique products. It's bulk goods. Cereals, coffee, cocoa, oilseeds, fruits. Even bananas alone exceed 1.2 million tonnes in imports. When you look at the manifests, it's warehouse food, not luxury food

- Commodities and primary products together account for nearly half of total import volumes.

- Tropical fruit demand keeps climbing, pushing steady container traffic.

- Processed products like juices and oils are growing as value-added segments.

- Organic food suppliers focusing on staples usually see more reliable turnover than niche players.

New suppliers are stepping onto the stage

The map of exporters is widening. Mexico, Canada and Colombia have shown strong growth in organic exports to the EU and US. Traditional supply bases are being joined by new ones. The trade feels less concentrated now, more distributed

- Mexico alone added tens of thousands of tonnes in additional exports.

- Canada recorded double-digit percentage growth.

- Buyers prefer multiple origins to manage risk and pricing.

- This creates space for emerging exporters who meet standards consistently.

Consumer behaviour makes imports inevitable

Some countries simply consume too much organic to rely on local farms. Switzerland spends about €425 per person, and Denmark about €384 per person annually on organic food. At those levels, imports aren't optional — they're necessary

- High per-capita spending reflects deep, stable demand rather than short-term trends.

- Domestic production alone cannot fill supermarket shelves.

- Import dependency creates repeat business for trusted exporters.

- Suppliers who maintain quality tend to keep these markets for years.

So why 2026 feels like the moment

Put it all together — €125 billion in sales, millions of producers, millions of tonnes crossing borders, steady import growth, widening supplier bases. Nothing flashy. Just quiet, persistent expansion. Like a river swelling after many small rains.

Conclusion

Organic agro exports aren't “trending” because of hype. They're trending because the math now makes sense. Buyers see organic as standard procurement, not a specialty risk. Certification has become basic compliance rather than a premium badge. Larger, multi-season contracts are replacing small trials. Exporters who step in now are likely to find this isn't a short wave, but a long current.