For over a decade, China has been the cornerstone of Malaysia’s palm oil export strategy, not only in terms of shipment volume, but also as a key driver of price signals, demand stability, and long-term market confidence.

-1.webp)

Yet, over the past five years, this once-steady trade relationship has undergone a more pronounced transformation than any other major edible oil corridor. Shifting feedstock preferences, changing price dynamics, and logistics-based competitiveness challenges have all forced Malaysia to reassess how it engages the world’s second-largest palm oil consumer.

The fall of Malaysia’s Palm Oil Export to China

Official data reveals a 49% fall in Malaysia’s palm oil exports to China between 2020 and 2024, followed by an additional 39% drop in the first ten months of 2025. What was once seen as a cyclical dip has now evolved into a structural reset. For palm oil traders, refiners, procurement managers, and policymakers, understanding this transition — and its commercial implications — is critical to navigating the next phase of global vegetable oil trade.

A Five-Year Slide That’s Redefining the Malaysia–China Trade Axis

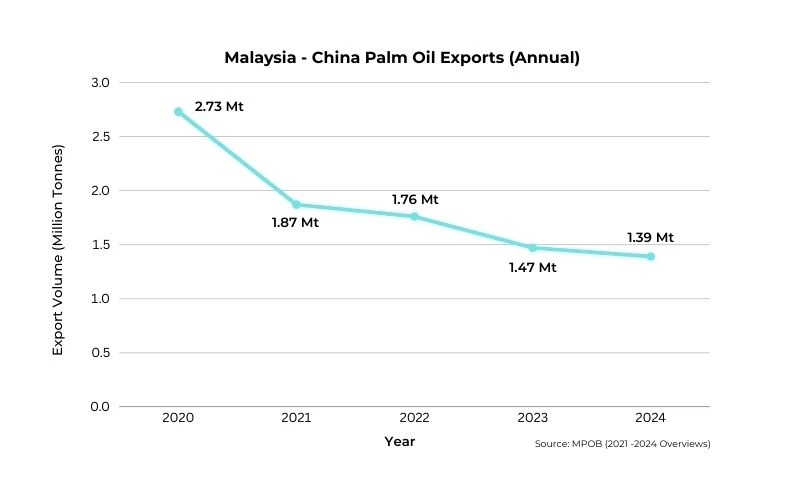

To appreciate the current downturn, it’s worth tracing the trajectory through official export figures from MPOB:

- 2020: 2.73 million tonnes

- 2021: 1.87 million tonnes

- 2022: 1.76 million tonnes

- 2023: 1.47 million tonnes

- 2024: 1.39 million tonnes

This consistent decline is no longer an annual anomaly. It reflects a multi-year structural shift shaped by China’s changing procurement patterns and evolving global price signals.

In Malaysia’s trade relationship with China, the most significant fall in palm oil exports occurred between the period 2020 to 2021. This time span witnessed a market full of volatility in which refineries witnessed tight profit margins, and the reason they diversified towards other Edible Oil operations. However, it is worth noticing that a turning point came in 2025, when the global demand for palm oil increased, and for a brief period, it started trading higher than soybean oil. Perhaps it was a rare price inversion that rapidly made China look for the soybean-based alternatives to cater to its refining sector, which is cost-sensitive, and the food processing sectors that are directly dependent on it.

2025: The Year of Inflection

Speaking at the Malaysian Palm Oil Council (MPOC) Industry Dialogue with Chinese importers, Minister Johari Abdul Ghani noted that Malaysia’s palm oil exports had fallen 39% in the first ten months of 2025 — a clear signal of deepening competitiveness challenges.

Several interlinked factors explain the decline:

1. Price Inversion with Soy Oil: A Direct Loss of Market Share

Palm oil’s long-standing cost advantage has always been its key selling point for Chinese refiners. When soyabean oil became cheaper, substitution happened almost immediately and on a large scale.

2. Logistics-Based Competitiveness Pressure

Higher freight rates, congestion at key Malaysian ports, and inconsistent vessel turnaround times increased CIF costs, making Malaysian-origin cargoes less attractive compared to rival suppliers.

3. Refinery Economics Shifting Against Palm Oil

Chinese refiners along the coast increasingly use flexible processing lines that automatically switch feedstocks based on landed cost. In 2025, soy oil simply fits their economics better. Together, these shifts undercut palm oil’s traditional edge in China’s highly price-driven procurement system.

Malaysia’s Strategic Reset: Rebuilding Confidence and Competitiveness

Recognizing the scale of the challenge, Malaysia has pivoted toward a more assertive engagement strategy. At MPOC’s networking event from 25–27 November, 37 Chinese buyers — representing around 2.5 million tonnes of annual demand — met with Malaysian producers and palm oil exporters.

This was not a routine promotional exercise. It was a deliberate effort to realign commercial relationships, gather buyer insights, and restore Malaysia’s competitive footing in a changing marketplace.

Malaysia’s renewed focus revolves around three pillars:

Greater transparency in pricing cycles

Offering better forward visibility on pricing and supply trends helps refiners manage risk more effectively.

Enhanced logistics reliability

Improving port efficiency, optimizing freight routes, and easing bottlenecks can lower landed costs and restore Malaysia’s competitiveness.

Long-term supply alignment

With China expected to maintain high edible oil consumption, aligning Malaysia’s output with medium-term industrial demand will be key to regaining share.

Looking Ahead: Scenarios for 2026–2028

Based on current data and 2025’s turning point, Malaysia’s palm oil export outlook to China could unfold in three broad scenarios:

- Baseline Scenario (Most Likely):- If palm oil regains its price discount and logistics improve, shipments could recover to 1.6–1.8 million tonnes, returning to mid-range historical levels.

- Optimistic Scenario (Stronger Price Advantage + Diplomatic Leverage):- If palm oil maintains a cost advantage of USD 80–120 per tonne over soy oil, exports could rebound to 2.0 -- 2.2 million tonnes, nearing pre-2022 levels.

- Risk Scenario (Persistent Competitiveness Gap):- If price disadvantages remain and soy oil continues to dominate, Malaysia may stay near the 1.3–1.4 million tonne range — similar to 2024 outcomes.

Conclusion

Malaysia’s declining palm oil exports to China reflect more than short-term market turbulence — they mark a structural realignment shaped by pricing, competitiveness, and evolving refinery economics. Yet, China remains one of Malaysia’s most strategic export markets. The presence of Chinese buyers representing nearly twice Malaysia’s current export volume underscores that recovery potential remains strong.

The next phase will hinge on how swiftly Malaysia can rebuild the fundamentals that once defined its market advantage: predictable logistics, pricing clarity, and supply alignment with China’s industrial demand cycles.

For the best global export and import opportunities of Palm Oil, Visit www.tradologie.com

.webp)