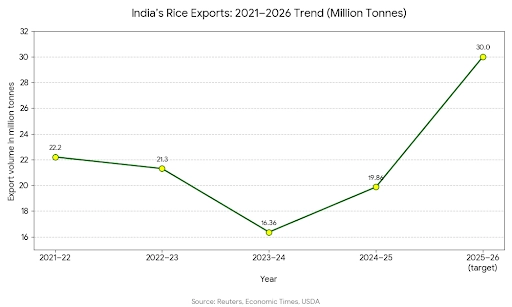

India's rice export narrative appears poised for its next big leap. After years of alternating between record highs and restrictive policies, the world's largest rice exporter is once again aiming high—with the Indian Rice Exporters Federation (IREF) outlining an audacious 30 million tonne export target for 2025-26.

Historical patterns: target vs delivery

Back in 2021-22, India's rice exports were close to 22 million tonnes, a high watermark before policy constraints intervened. But subsequent periods saw drastic regression. From September 2023 to August 2024, rice exports slumped to just 14.3 million MT, a drop of nearly one-third from 21.3 million MT in the prior year.

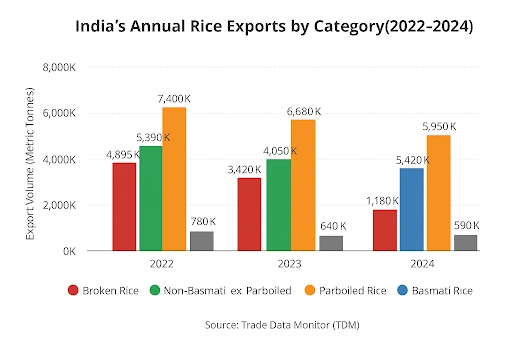

The contraction was especially steep for non-basmati white rice (excluding parboiled), which plunged by 5.4 million MT (-87%), and broken rice, down 0.78 million MT (-57%). Parboiled exports also fell by 1.7 million MT (-20%) due to heightened export duties. Basmati, by contrast, remained resilient: it recorded a gain of 0.885 million MT (≈ +18 %) over the same period.

In the FY25 period (April 2024 to March 2025), however, India appears to have rebounded somewhat. By March 25, 2025, total rice exports stood at 19.86 million tonnes—well ahead of the FY24 levels (16.358 million tonnes). That jump suggests exporters are regaining confidence and that structural constraints may be loosening.

Meanwhile, for 2024/25 the USDA projects final shipments to land around 18 million tonnes, reflecting a moderate recovery but still far short of the 2021-22 peak.

Thus, any aspiration toward 30 million tonnes must first confront this recent volatility, and the substantial gap between what was projected and what was realized.

Why the 30 Mt target—and what underlies it ?

The 30 Mt figure stems from renewed confidence. With a likely record domestic crop (estimates ranging in the 145 million tonne band) and building stocks, exporters believe the supply cushion is large enough to support aggressive export bulk rice pushes. It has been noticed that the government has committed to avoiding new export curbs, barring emergent food security pressures.

If realized, 30 Mt would represent a 50+ % jump over recent export levels and reassert India's dominance in the global rice trade landscape, potentially putting downward pressure on international prices.

Structural headwinds: Is 30 Mt realistic ?

Despite the bullish rhetoric, several structural and strategic challenges make the 30 Mt ambition a stretch.

Global demand & competition still tight

Global rice trade is projected to rise only modestly—USDA forecasts place global trade at 53.8 million tonnes for 2024/25. With multiple exporters (Thailand, Vietnam, Pakistan) competing aggressively, India cannot simply dump supply without pushing price and margins downward. After India's 2024 export easing, global rice prices already slid, prompting competitors to discount.

Price floors, export duty regimes, and policy risk

Though India recently removed the floor price for non-basmati white rice and scrapped the export tax on parboiled rice, these policy levers have in the past been used for supply control. Meanwhile, basmati rice had its minimum export price (MEP) removed only in late 2024 to revive its competitiveness. The latent risk: any new food price pressures or crop failure may prompt rollback of liberal policies.

Logistics, quality, and varietal fit

Bulk rice exports demand efficient supply chains, cold logistics, port infrastructure, and compliance with phytosanitary regimes in key markets (e.g., Africa, Middle East). India's vast geography imposes bottlenecks. Further, some global importers prefer broken or discount grades; India must calibrate its portfolio to market segments rather than solely volume.

Currency, margins, and external headwinds

A weaker rupee may assist competitiveness, but exporters also face rising input, energy, and freight costs. On top of that, new trade barriers emerged: the U.S. recently imposed a 25% tariff on Indian rice (mainly targeting basmati), though it accounts for only a small share (~2.34 lakh tonnes) of Indian basmati exports.

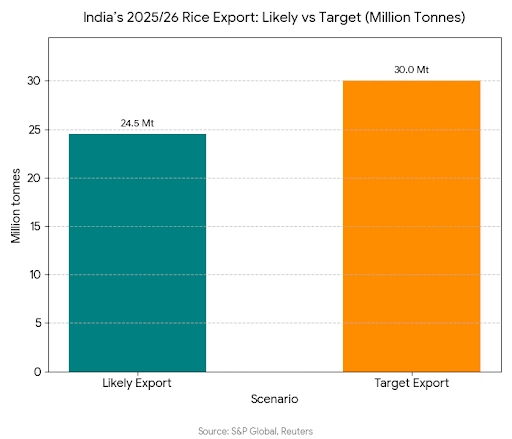

Projection: Stretch but not impossible

Given historical volatility, institutional constraints, and market realities, 30 Mt is a stretch goal, not a baseline expectation. A mid-path scenario around 24-26 million tonnes seems more credible, aligning with IREF's internal projection (24.5 Mt) and incremental growth trajectories.

If India were to approach 30 Mt, several conditions must align:

- A strong domestic crop (ideally ≥ 145 Mt) with low domestic price inflation

- Continued liberal export policy (no renewed curbs)

- Infrastructure investment to streamline logistics and reduce transaction costs

- Market discipline in pricing to avoid undercutting margins or triggering trade retaliation

- Strategic targeting of growing import volumes in Africa, Middle East, SE Asia

In that event, India could once again reshape the global rice trade—offering bulk Indian rice, marginalizing rival suppliers, and exerting downward pressure on global price benchmarks

Yet in the B2B trade calculus, what matters is not the headline target but consistency, predictability, and supply reliability. Even a 25 Mt outcome would be a formidable leap and reshape supplier dynamics, provided India can avoid the boom-and-bust policy swings of past cycles.

Conclusion:

In short, India's 30 million-tonne rice export ambition is both bold and emblematic of its renewed global trade confidence. The target reflects an intent not merely to reclaim lost volumes but to reaffirm India's dominance in the global rice trade, particularly in Bulk Non-Basmati and premium basmati segments. However, realizing this ambition will require near-flawless coordination across agricultural productivity, export policy, and trade infrastructure. Stable government policy on export duties and minimum export prices, coupled with efficient port operations and sustained buyer confidence, will be key.