The global wheat trade rarely shifts overnight. It moves quietly, through procurement decisions, pricing adjustments, and small changes in how food and feed industries source their raw materials. But every now and then, a market makes its intent clear. The Philippines is doing exactly that.

For exporters tracking global wheat importers and global wheat buyers, the signals coming out of the Philippines over the past year are worth paying attention to — not as a short-term spike, but as part of a structural import story that keeps gaining momentum.

A Market That Imports What It Eats

The Philippines does not grow wheat domestically. That single fact shapes everything about its role in the global wheat trade. Every loaf of bread, every pack of noodles, every feed formulation that includes wheat starts with imports. There is no buffer of local production to fall back on.

Since there’s no domestic wheat production to lean on, the Philippines watches its import numbers closely. Recent assessments from the USDA’s Manila office suggest that the country is heading toward around 7.4 million tonnes of wheat imports in 2025/26, compared with 6.35 million tonnes last season. A rise of this size doesn’t come from forecasts alone — it reflects orders already moving through the system.

The forecast was revised upward after stronger-than-expected buying from both the food processing sector and the animal feed industry. In other words, wheat demand isn’t coming from one corner of the economy — it’s spread across how the country eats and how it feeds its livestock.

Feed Wheat Is Doing the Heavy Lifting

Looking at trade data between July and October 2025 helps explain where the pressure is coming from. During that period, feed wheat accounted for about 52% of total imports, while food wheat made up roughly 45%. The remaining 3% came from other wheat products.

That split matters. It tells global wheat buyers something important: this isn’t just about bread and noodles. It’s also about how feed millers are reacting to relative prices.

USDA-FAS Manila noted that feed wheat gained share because import prices softened at a time when corn prices stayed elevated, particularly between February and August 2025. Wheat stepped in as a substitute, not because food demand weakened, but because feed formulations became more flexible.

This is how substitution really works in practice — quietly, spreadsheet by spreadsheet, ration by ration.

Swine Recovery Adds Another Layer

There’s another piece to the feed story that exporters should not ignore. The Philippines’ swine industry has been gradually recovering, and that recovery brings feed demand with it.

As feed wheat prices became more competitive relative to corn, wheat found its way into rations more often. That trend could continue, especially if feed wheat maintains its price advantage. USDA-FAS Manila did flag a caveat: if corn prices drop meaningfully, the pace of feed wheat imports could cool. Relative pricing, not ideology, will decide.

Still, for now, the direction is clear enough to matter.

What the Numbers Say

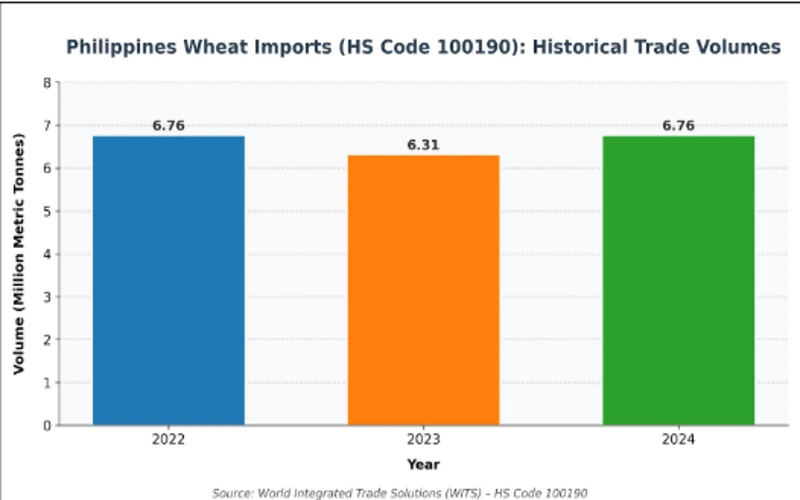

Looking at import volumes under HS Code 100190, the trend holds up over multiple years:

- 2022: ~6.76 million tonnes

- 2023: ~6.31 million tonnes

- 2024: ~6.76 million tonnes

The dip in 2023 didn’t last. Imports rebounded, and the forward projections suggest that 2025/26 will move well beyond earlier ranges. For global wheat importers, consistency matters more than year-to-year noise.

Why This Matters for Exporters

From an exporter’s perspective, the Philippines ticks several boxes at once. It’s import-dependent, price-sensitive, and diversified in end use. Food manufacturers need stable quality wheat for milling. Feed millers need flexibility, volume, and competitive pricing. Neither side can pause buying for long.

That combination creates room for exporters who understand specifications, logistics, and timing — not just price. In the global wheat trade, reliability often matters as much as being cheapest on paper.

The Philippines also doesn’t rely on a single origin in the long run. That opens the door for multiple exporting regions to participate, provided they can meet technical and commercial expectations.

Food Demand Isn’t Going Anywhere

It’s easy to focus on feed wheat because the growth rates look sharper. But food wheat demand remains steady and deeply embedded. Bread, noodles, biscuits, and other wheat-based products are not fringe items in the Philippine diet anymore. They’re everyday consumption goods.

That stability matters to global wheat buyers who prefer predictable demand over flashy growth. Food wheat imports may not surge dramatically, but they don’t disappear either. They form the base layer of the market.

A Market That Rewards Attention

The Philippines isn’t a speculative destination. It’s a working market. Buyers there respond to price signals, yes — but also to supply reliability, contract discipline, and shipment performance.

For exporters already active in Southeast Asia, the country fits naturally into regional trade flows. For those looking to diversify their buyer base, it offers scale without excessive volatility.

Final Thought

Rising wheat imports in the Philippines aren’t a headline designed to excite traders. They’re a signal for exporters who read demand patterns instead of chasing trends. In the global wheat trade, that’s often where the real opportunities sit — not loud, not dramatic, but steadily compounding.

For global wheat exporters, importers, and buyers watching Southeast Asia, the Philippines is no longer just a routine destination. It’s becoming a market that quietly shapes volume decisions across the supply chain.